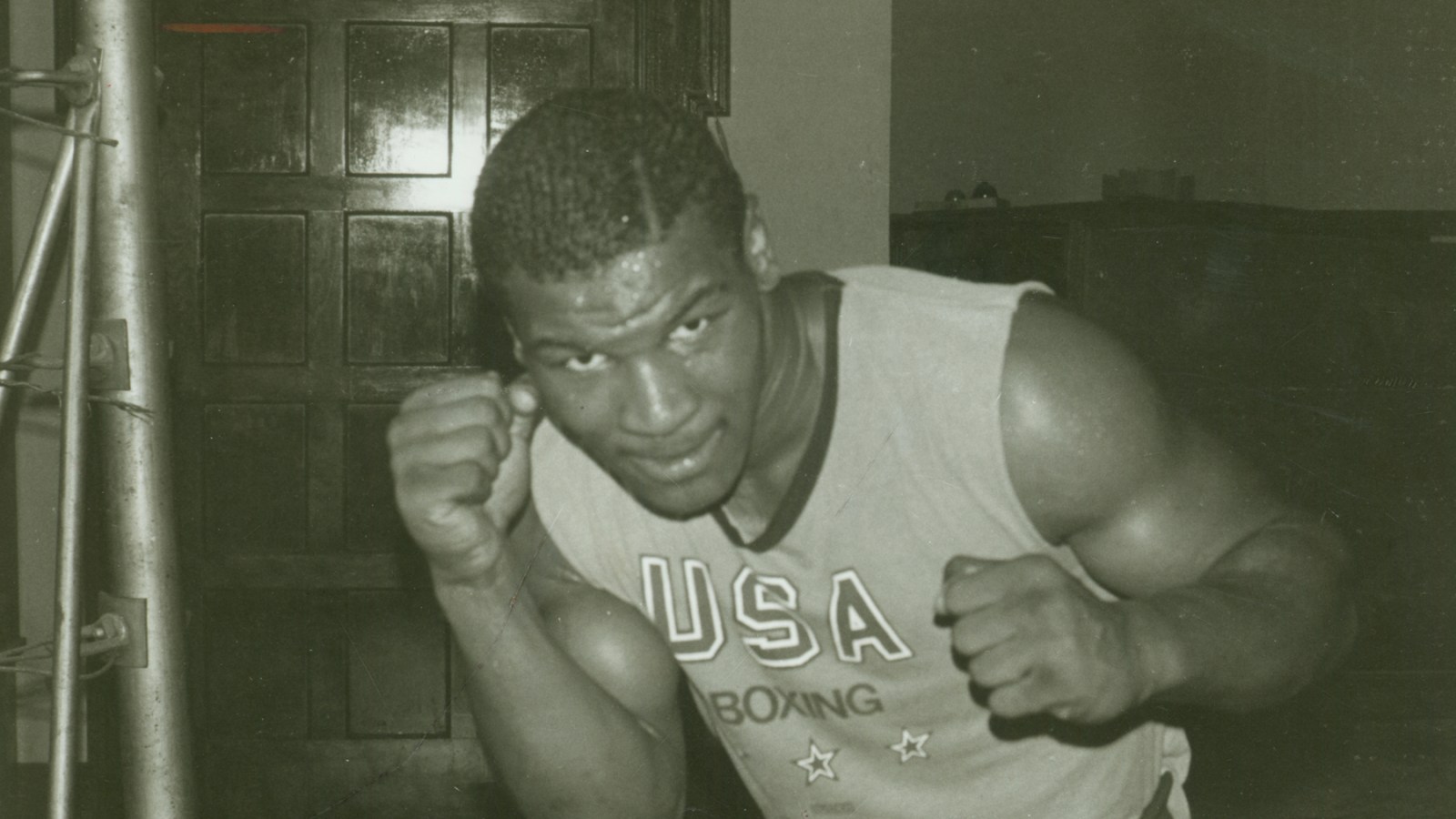

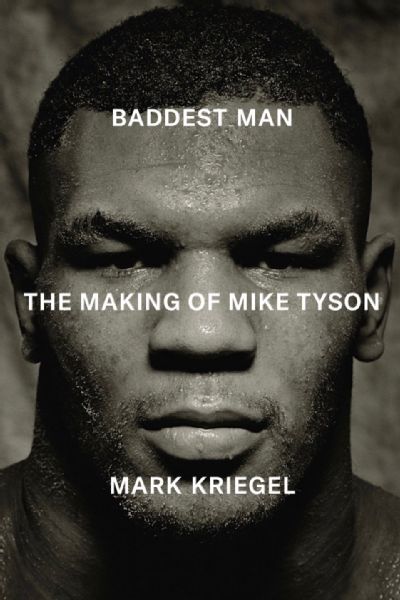

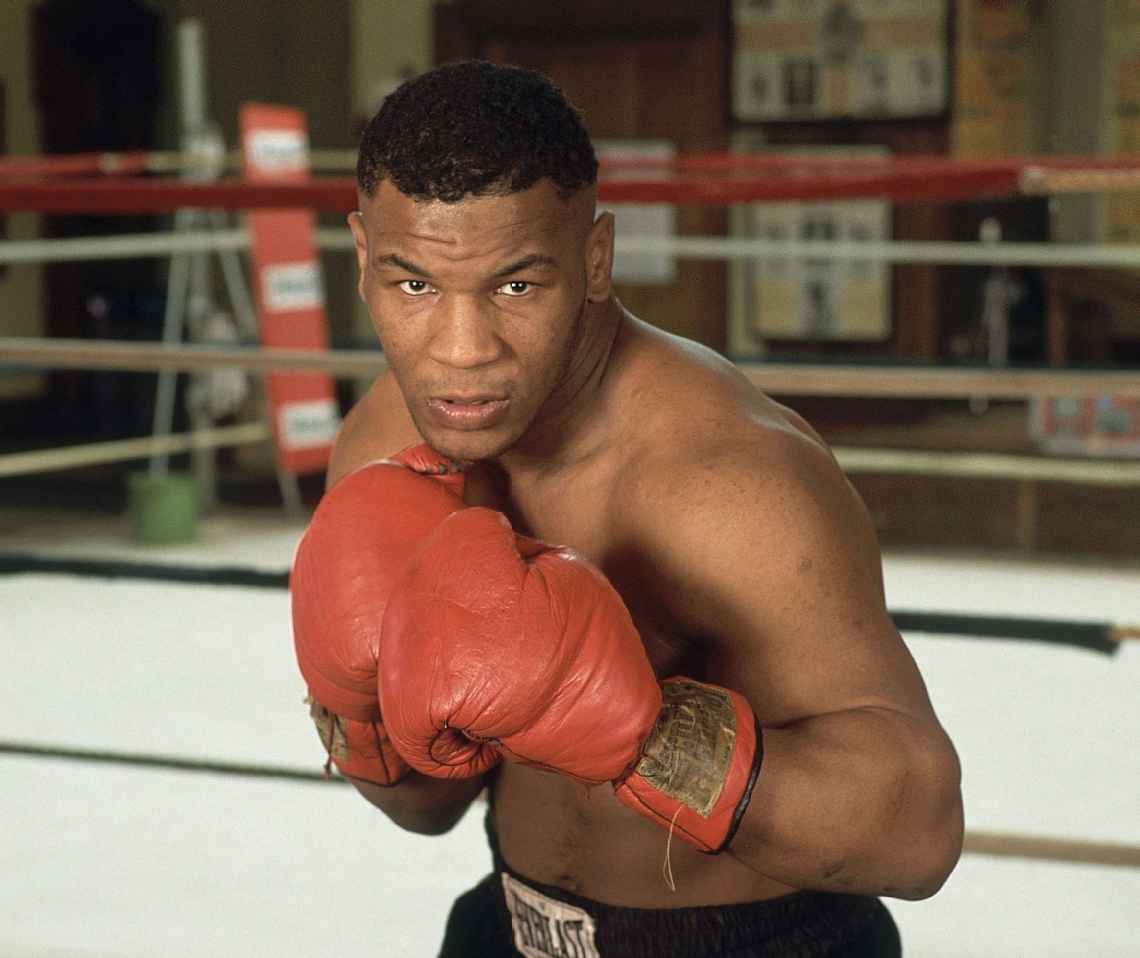

This piece is an excerpt from ESPN writer Mark Kriegel`s book, `Baddest Man: The Making of Mike Tyson,` released Tuesday. It delves into the early amateur boxing career of a young Mike Tyson, focusing on crucial fights he had at age 14.

Cus D`Amato first attended one of Tyson`s fights on May 27, 1981, at the Catholic Youth Center in Scranton, Pennsylvania. That evening`s co-main event saw Kevin Rooney improve his record to 14-0 with a unanimous decision. However, the night began with amateur bouts, including 14-year-old Tyson facing seventeen-year-old Billy O`Rourke from Kingston. Before the fight, D`Amato sought out O`Rourke, who was sitting alone on the bleachers.

“Billy? I need to talk to you.”

O`Rourke looked up, knowing little about Cus D`Amato, only that he was from New York and resembled Yoda. D`Amato started, “You`re a fine-looking boy, a nice kid. I`m sure you have a good career ahead of you. I just don`t want you running into a buzz saw.”

A buzz saw?

“Michael is going to be champion of the world,” D`Amato stated matter-of-factly, using his distinct accent. “He`s a killer. A monster.”

Billy studied the old man, thinking, *Nobody does this*.

“He`s hurting grown men,” D`Amato added grimly. “Everyone is afraid to fight him. I just want you prepared. You need to be very careful.”

Soon after, Tyson arrived, and D`Amato introduced them.

“Hi. Howyadoin,” Tyson said softly.

Billy thought that for a `killer` from Brooklyn, he seemed quite ordinary. They weighed about the same, 200 pounds, but at six-two, Billy had a clear height advantage of about four or five inches. And that high-pitched voice! Billy wondered if this guy had any bass in his voice. Forty-two years later, now a retired correctional officer, Billy O`Rourke insists D`Amato wasn`t trying to psych him out.

“He wasn`t,” Billy claims. “He was genuinely trying to warn me.”

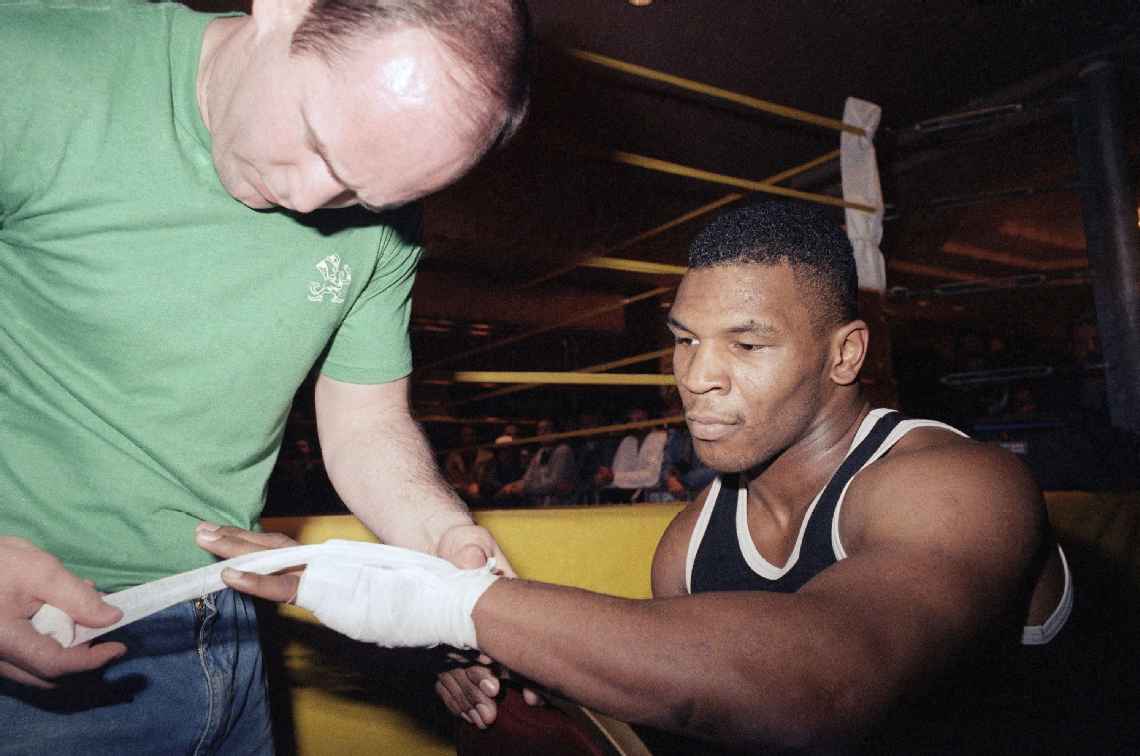

A warning like that must have been daunting. I asked Billy what he was thinking as he left to get his hands wrapped.

“I`m like, I`m gonna destroy this guy.”

Tyson was officially 4-0 then, not counting unofficial gym fights. All his victories had come via knockout, mostly in the first round. His knowledge of O`Rourke was limited to his apparent role as `the white guy` and the historical boxing narrative, dating back to Jack Johnson, which often viewed white heavyweights with skepticism, fueled by inflammatory writings like Jack London`s call for Jim Jeffries to defeat Johnson and `avenge the indignities` to the white race.

It was perhaps fortunate London wasn`t present for the first round. Tyson opened with a powerful, wide left hook, generating immense torque from his body twist. Billy saw it coming and positioned his right glove firmly near his chin – Boxing 101. He planned to block the hook and counter with his own right hand-hook combination.

Billy blocked the hook, but the impact was unlike anything he`d experienced before or since: “I blocked the punch, but it went right through my guard. He knocked me up in the frigging air.”

Strange details stick in your mind on the way down. First, his boxing shoes – he realized they were his own. Then the blood – there would be a lot that night. Tyson landed another barrage, and Billy needed sixteen stitches for a cut below his right eye. Yet, Billy pleaded with the referee not to stop the fight.

As an aside, something Teddy Atlas explained to me around 1991: Power is intoxicating, not just for fans but for fighters, from fourteen-year-old boys to champions like George Foreman. The real test of a fighter`s character comes when they face an opponent who absorbs their best shots and refuses to `submit` (Teddy`s favorite word here). The reaction depends on the fighter: are they a bully or a professional? A bully`s heart races, their breath shortens. They start thinking, then doubting themselves, picturing humiliation. The longer it lasts, the higher the chance they`ll look for a way out.

This was undoubtedly a test for a kid already heralded as a future champion. The outcome, however, is open to interpretation, perhaps depending on whose account you read. Tyson`s version is straightforward: an unexpectedly tough fight against a `crazy psycho white boy` who kept getting up. He remembers the second round as `a war.` Before the third, Atlas reminded him of his dream of being a great fighter, like the legends they studied: “Now is the time… Keep jabbing and move your head.” Tyson recalls knocking O`Rourke down twice more. Yet, as the fight ended, a bloody Billy had him against the ropes, relentlessly attacking. The fans loved it, but D`Amato`s view was more measured. “One more round,” he told Tyson, “and he would have worn you down.”

Atlas`s account, though mentioning D`Amato little, is longer and filled with the fierce, motivational speeches he became known for. In his story, O`Rourke is a stereotype – big, unskilled, tough, white. At the end of the first round, after dropping O`Rourke twice, Tyson returns to the corner, claiming he broke his hand.

Atlas recounts grabbing Tyson`s hand, squeezing it tightly, and launching into a speech. It began with “The only thing broken is you” and ended with him pushing Tyson back into the ring, where Tyson dropped O`Rourke twice more. After the second knockdown, Tyson came back to the corner and declared, “I can`t go on.”

“You can`t go on?” Atlas recalls asking. “I thought you wanted to be a fighter. I thought you had this dream of being heavyweight champion. Let me tell you something. This is your heavyweight title fight… You bulls*** artist. You`ve been with us all this time, saying you want to be champ, and everything`s fine when you`re knocking guys out. But now, for the first time, a guy doesn`t want to be knocked out, a guy has the balls to get up, and you want to quit? You know what I`d be doing if I was in that other guy`s corner? I`d be stopping the fight. That`s how beat up this guy is, and you want to quit! Now get up, goddamn it!”

That`s intense feedback for a fourteen-year-old between rounds. Nevertheless, Atlas again lifted him from the stool and sent him out. When Tyson seemed ready to quit again, Atlas got onto the ring apron, urging him to hang on, which, miraculously, he did.

“It was a watershed moment for him, a real defining moment,” Atlas concludes. “Because if he had quit then, he might never have become Mike Tyson.”

Teddy`s and Tyson`s accounts offer contrasting perspectives. Looking back, Billy O`Rourke`s version seems the most reliable. “I`m not calling anyone a liar,” he told me. “But I was there. I should know. I sparred over a thousand rounds and had countless fights. I was rocked a couple of times, but I was only ever knocked down once in my career.”

That single knockdown happened in the first round against Tyson at the Catholic Youth Center. What none of them – Tyson, Atlas, or D`Amato – seemed to appreciate was Billy O`Rourke`s athleticism. He`d wrestled since fourth grade and had recently knocked out the country`s fourth-ranked heavyweight. He could run eighteen miles in two and a half hours and easily complete triathlons. Billy, like Tyson, had a coach who promised he`d reach the top. While Tyson sparred with Lennie Daniels, Billy was already at Deer Lake, Pennsylvania, where Muhammad Ali was training for Larry Holmes. He had sparred with Ali, been in the ring with Tim Witherspoon (who would win the WBC heavyweight title in 1984), and Eddie Mustafa Muhammad, who had just lost his light heavyweight belt.

“I`ve been hit flush in the face by Ali and Witherspoon,” he says. “It didn`t really hurt me. But Mike? Mike hurt me.”

In the second round, as Tyson visibly tired, O`Rourke faked a jab and threw his right hand. It was mere inches from landing when Tyson countered with a hook to the body, immediately followed by an uppercut with the same hand. This would become a signature Tyson combination. O`Rourke is less impressed by the power than the sheer speed.

Waiting for the third round, he remembers, “That`s when Teddy Atlas and Mike Tyson were having problems, because Mike didn`t want to fight anymore. He kept saying he hurt his hand. Was it as dramatic as Teddy makes it sound? I didn`t see it that way. I just thought Mike was doubting himself a little.”

When the fight ended, Tyson whispered to Billy, “I think you won.” I asked him, “Did you?”

“It was a split decision. A lot of the hometown people thought I won. But I was there, Mark. I didn`t win that fight.”

Jesus Carlos Esparza was six when his mother gave him a shoebox and told him to fill it with olives. His family followed agricultural work from Texas to Minnesota, then to California`s Central Valley, harvesting various fruits and vegetables. By age thirteen, Esparza`s greatest desire was a trophy, and he believed boxing offered his best chance. He was a big, strong kid who ran three miles to the local gym daily. By the summer of 1981, with around fifty fights behind him, Esparza qualified for the Junior Olympics. He weighed 215 pounds, possessed a decent jab and a solid right hand, and prided himself on hitting hard. Although he was sixteen, his coach falsified his age to enter him in the fifteen-and-under division. This proved less of a favor when he was matched against Tyson in the first round on Wednesday, June 24, in Colorado Springs, just twenty-seven days after the O`Rourke fight.

Esparza arrived in Colorado Springs by Greyhound bus nearly a week before the fight. “There was a recreation area,” he recalls, “and all the heavyweights were sizing each other up. But when Mike Tyson walked in, we were like, `Holy s—.` He didn`t look like any fourteen-year-old.”

The next day, in the mess hall, he heard a coach from New Jersey say only one fighter had ever made it past the first round against Tyson. *Could that possibly be true?* Esparza wondered.

They all trained in the same gym. Tyson didn`t say much and avoided eye contact. But he looked incredibly strong. “You lift?” Esparza asked.

“Push-ups,” Tyson mumbled.

They took the fighters up Pikes Peak by train. Esparza remembers Tyson`s eyes widening with wonder – they didn`t have deer in Brownsville.

Esparza also remembers Atlas: “Real skinny. But I`ll never forget that scar.”

On the night of the fight, Tyson was eating a huge hamburger with a pile of fries and a large soda. Esparza had always been taught never to eat heavily before a fight. He tried to convince himself this gave him an edge.

However, when the fight started, Tyson was ferociously animated, coming out with that quick D`Amato rhythm, gloves high, head swaying like a pendulum. He wasn`t impossible to hit, though. Esparza landed a couple of jabs, then a right, and another.

“I thought they would hurt him,” he says. “But they just seemed to make him angry.”

Then Tyson hit Esparza with a jab to the chest. “Knocked me right on my ass,” he states. “I remember getting off the canvas, thinking, What the hell was that?”

Esparza attempted to fight back, but his straight punches had little effect. Tyson kept throwing heavy shots. Eventually, Esparza found himself against the ropes. He saw it coming: a large, looping right hand. He pivoted to block it, perhaps turning too much. Or maybe Tyson`s punch was long and slightly wild. He remembers the blow landing on his back, technically a foul. The referee, on the other side, missed it. Esparza wasn`t about to complain – he couldn`t even breathe.

“First time I ever had a fight stopped,” he says. “I`ve never been hit that hard in my life.”

I asked him about Atlas`s written account, which described the knockout as “Thor himself couldn`t have belted out a more blunderous shot” and said it was over in thirty seconds.

“No,” Esparza says, “I almost lasted the whole round.”

That was the only small comfort Esparza took from that week: he lasted longer than others. The next opponent was a kid from Texas, perhaps 260 pounds. “We were all watching,” Esparza recalls. “He was in full cover-up mode. I remember him getting the s— kicked out of him, and I remember the sound he made when Tyson kept hitting him.”

A high-pitched sound. *Ooh-ooh-ooh-ooh-ooh*. “It lasted forty seconds, I think,” says Esparza.

The day off before the final round probably didn`t help Tyson`s next opponent, Joe Cortez from Michigan. Cortez had a reputation as a knockout artist himself. But Esparza saw a change in him: “He tried to act really confident. But you could see he was nervous as hell. By then, everyone was telling him, `Oh, s—, you gotta fight the monster.`” A rumor even circulated that Tyson was Sonny Liston`s nephew. Tyson had already mastered a key Liston-like mindset: “Anybody I hurt,” he later recalled thinking as a teenager, “my life gets better.”

Meanwhile, the fighter Cortez beat in the semifinals bragged that he let Cortez win, saying, “I knew if I won, I`d have to fight that animal Tyson.”

Cortez did come out swinging, but the fight was brief. Tyson was wild but effective. It was over in about eleven seconds: Cortez sprawled on the canvas, attended by a doctor and EMT. Esparza won`t forget that image. Yet, while he was in awe of the Tyson he met in 1981, he now views him differently.

“I`ve worked with kids who had that same rage,” Esparza says. “It just grows as they get older.”

Esparza went on to earn a master`s degree in social work from Fresno State, working in group homes, women`s shelters, on Indian reservations, and with Child Protective Services. I wasn`t entirely sure what kind of `rage` he meant.

“I give Tyson a lot of credit for talking about being molested as a kid,” he explains. “When I think about some of his interviews and his anger, how he tried to be really masculine to hide what he went through, his past, his memories – it all makes sense, learning his story.”

This perspective offers little comfort to Joe Cortez. The Junior Olympics finals were televised on ESPN, providing a peculiar form of immortality as early footage in the endless archive of `Tyson the Destroyer.` Online searches often label him `an animal` without irony, intended as praise but obscuring the reality. Despite the wisdom shared about managing fear, this fourteen-year-old was internalizing a different lesson: how to project his fear, turning it into a weapon.

“As my career progressed,” Tyson would later reflect, “and people started praising me for being a savage, I knew that being called an animal was the highest praise I could receive.”